A Slow Burning

There is a homestead that hides behind the majestic mountains of the rural Eastern Cape. There the people, trampling on their cracked feet, roam the vast landscapes. They share their time, sunlight and laughter with livestock, and conversations always lean toward the trivial things. The children drive their wire cars in oblivion to the anguish they will eventually inherit. Caught between the thoughts of tomorrow and of forever, the wheels are made from cans cut in half then cleverly assembled—nothing must go to waste. Wisdom trickles through the wrinkles of grandparents, and is passed down from generation to generation.

Seven years had lapsed since Ayanda matriculated and left home with a bag of hand-me-downs. Even he, in time, would soon bequeath these to his two younger siblings, Siyasanga and Andisiwe. The day Ayanda left for university, his grandmother’s hard eyes welled up with tears. The soft crescents under her eyes had drawn like shopping pouches slacked with the weight of coins, but in her case, they were slacked with years of harsh poverty.

Ayanda’s mother, Zukiswa, passed away soon after delivering Andisiwe. The doctors in the hospital called it a postpartum tragedy, a silent infection that killed a seemingly healthy patient. No one really knew what that meant. Life went on after. Their grandmother—Mama to them—raised the three boys. Her warm embrace, pregnant with hope, love, playful scoldings and heated prayers troubled Ayanda’s mind that Friday.

“Open the bottle and play, my brother.” Said Lungelo’s eager voice, ready for a challenge. They were playing a game of pool at a tavern adjacent to the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in Port Elizabeth.

“Moja, bhudda” — “alright, brother,” came a reply from Ayanda, the thought of Mama hidden very well behind the slightly inebriated façade. Ayanda met Lungelo in a Reinforced Concrete Design class after the lecturer, Mr Zulu, handed the pair their test scripts last, an obvious sign to the class and to them that they had failed the test. They met again at a Fluid Mechanics and Hydraulics lecture, both taught by the same Mr Zulu. Though the two had been in the same course for six years—now seven. They had never really acknowledged each other. But pain like what they both felt can rarely ever be denied; it sat like a magnet pulling closer to itself only those who could understand it.

Razor was a nickname Ayanda had earned in high school. He matriculated with a bachelor’s degree adorned by 7 distinctions, and so did Lungelo. Ayanda was a razor-sharp blade that cut through every calculation, case study and problem presented to him. On this day, Ayanda held the cue stick at a 90-degree angle from the cue ball. He was about to make a c shot. If done right, the white ball would skillfully glide past the others in a c and go straight to the one it was intended to hit. This was a trick years of playing pool gifted him. It was a show off move. At the success of the shot, the lads watching the game took their hats off, some handed him congratulatory cigarettes and others offered them a few more beers. Ayanda’s haughty eyes looked back at Lungelo, and Ayanda shrugged and smiled.

“For humiliating me like that, the next round is on you,” laughed Lungelo as he accepted the palpable weight of loss. The day was going as usual. A clear skied afternoon, the sun dancing in the firmaments and chuckles that mitigated the thorns of insignificance and time. Taverns have that air about them; though nothing is okay, everything, with a beverage in hand, is perfect. For a second, everyone is who they wish to be and those who can’t handle their liquor are who they truly are.

The chairs were in perfect shade, fairly far off from the tree that reeked of urine. And in the indistinct chats in the background was the air of boastful nothingness where egos thrived on who could gorge themselves more on alcohol, who was a timid drunk or, when last they had sex and how many virgins they deflowered. Meanwhile, Ayanda’s mind drifted toward the more important things, details of his life that he could not deny. He thought about his home. The primitive four-walled house conjured out of unbaked earth. The debilitated corners eroded by years of rain and unskilled patches. They cracked open like a slit of a model’s dress. The paint had long been erased by the scorching sun of the veld revealing the nakedness of the brown earth, bare, one or two wild storms away from collapsing. The roof was reinforced by logs and rocks that prevented it from flying away with the wind. Xhunta, a village far away from where he was that day, yet so close to everything he was.

“When is our next test, boy?” asked Ayanda.

“We have Mr Zulu for Fluid Mechanics Monday, sonny,” responded Lungelo.

“Don’t worry,” he added. “It’s not like we can fail any better,” and the two burst out in laughter.

***

A year earlier, Ayanda’s dad, Mjongeni had returned with a lung disease from working in the mines. Black lung disease, also called coal workers pneumoconiosis unfortunately for Mjongeni, had no cure. The Deep Mine of The South in Johannesburg left him with a pay-out that could not possibly last a period of five years. His pension fund wouldn’t even be enough to renovate his crumpling home. After his diagnosis, the company management told him his time to go home had come, and they’d employ the next fit member of his family in his place. Of course, it was business, nothing personal. Ayanda was the next candidate but he had no desire to be a miner, even so at the mention of his estranged father. He considered it an insult—that his father would vanish for years, then come back to fill the void with an offer of hardship and attenuated pay. For years, Ayanda and his siblings had to stomach ridicule from the whole village after their father left. Wouldn't growing up in a village afford him the insight of what his children would go through without someone to protect them? What did he think they ate? Looked like? Smelt like? Ayanda and his siblings all lost something that year of 2005. They lost eyes that beamed like stars at night, and smiles that carried the whispers of a full moon. They lost a love that cushioned their insecurities and nourished their hearts. Ayanda was just 14, Siyasanga 6 and Andisiwe a few weeks old. And that is how a slow burning began.

Ayanda was 24 when his father returned. By this time, everybody in the village had anticipated that Ayanda would be done with his Civil Engineering degree. He was a smart boy—he even came out in the papers as one of the top students in matric in the Eastern Cape region in his first year. He was the talk of the village then. There was no doubt he would finish his degree in record time. But nobody really knows the path more than the one who walks it, and the whip hurts most on the flesh it meets with.

Want to come back and finish this later?

“Wenza unyaka wesingaphi kanene ngoku ndoda?”—“What year is it that you’re doing again, boy?” asked a woman Ayanda didn’t even know one weekend as he returned from uMgidi of a neighbour in the village. The woman wasn’t alone, she was with a friend of hers. They both looked tired and their walking sticks begged to be freed from supporting their weights.

“I’m only left with two modules Gogo and I’m done,” replied Ayanda. The two friends didn’t even seem to care about the response as they continued on their way. Ayanda heard them whispering to each other in the distance:

“Tshotsho, wayecinga ukuba ubhetere kunabethu abantwana kaloku.” —“Serves him right, he always thought that he was better than our children.”

***

Mr Zulu wore his tired face to class that day. His grey eyebrows were on the verge of completely fading out. He had on a grey shirt tightly covering his large stomach. Everybody respected Mr Zulu, except the pretty girls, some of whom he was rumoured to have been intimate with. And who could blame them? Everybody knew exactly how dire their troubles back at home were, and Mr Zulu was a Head of Department that made sure you felt his wrath when you crossed him. These kind-hearted beauties would pity the less desirable and male students and tell them what would be in the exams. The exams were simple, test one and test two, and in a normal world everyone would pass. But Mr Zulu didn’t work like that— at the beginning of the semester in his introductory lecture, he would boastfully proclaim that there’d be some unfortunate students who would grow old with him in class and glare askance at his victims. Lungelo and Ayanda had become determined to somehow make it through his class. The rest had quit to other courses, and some dropped out of school completely. In class, Lungelo and Ayanda slid through Mr Zulu’s recycled jokes with an indifference for a repeated show. They already knew how they’d go, his subtle unsavoury analogies, exactly where in his face the wrinkles would set when he burst out laughing. It was straight after one of such classes in the beginning of their seventh year of repeating that Lungelo suggested that the two go get beers and make each others’ acquaintance. Friday afternoons at the tavern became a usual thing for the duo when one of them, if not both, had some money. They both had some that week, so they stayed long, and talked much. Ayanda had two part-time jobs where he waited tables to afford rent and make ends meet. At times from tips, he’d make just enough and send some home.

“So, my brother, what do you say about Lindiwe?” enquired Lungelo.

“What is there to say man?” came a reply.

“You know she likes you.”

“I know,” said Ayanda.

“So?” pondered Lungelo.

“Look chief, Lindiwe is just in love with the idea of me.”

“There you go again! Whatever it is you’re going to be sentimental about, save it,” Lungelo had had enough of Ayanda’s philosophical ideologies for one day.

“Okusalayo!” rebutted Ayanda and the two chuckled.

The cold beer in their glasses made the atmosphere in the terrace where they sat somewhat bearable. Soon, the horizon called for the sun and evening bid an elated “hello”. The regular customers returned from work and the tavern was getting full, a signature that night had taken off. The duo’s slight inebriation was gradually giving in to complete intoxication. The truths of the two’s lives laid in an invisible yet intimate place. The truth of an oppressive system at work laid bare gawking at everyone: the conversations men eagerly gathered to have and the recycled insipid ideologies that objectify women; anything to take their minds off their sad realities. The heirloom of worthlessness, senselessness and brutal poverty. For Ayanda, how his father left them as soon as their mother died and never supported them afterwards was enough to give him sleepless nights. How could one ever believe that the stars they were looking for had always been in them all this while?

***

The scorching sun of the veld is unforgiving in the summer, so much that the heat pushes dwellers to seek refuge under straw hats or umbrellas. Maize fields flourish and the prairies are evergreen. The rivers, due to the heavy rain, run wild and free.

Ayanda’s father’s chair sat just outside the door by the dusty Aloe plant. The ground was so dry and plain that there was no sight of grass, only cobbles. The mask from Mjongeni’s breathing machine covered half of his lower face and the machine took refuge inside the house. It was a day since he got back. It was recess for Ayanda, a holiday he spent mostly in other peoples gardens for money.

“You were present in our lives only because you thought you were returning a favour to our mother. If you actually cared for us, you would not have chosen to leave when she died. Why would any father leave his children at such a time in their lives?” said Ayanda as he headed off to work.

His father, appalled and short of breath, couldn’t say a thing.

Working in the garden, Ayanda's sad eyes couldn’t hide it anymore. In the heat, alone they began to sing, it was a tune of salt and water. The soil seeped through his fingers as he got rid of the weeds and he embraced the embers of a slow burning.

***

Mama, his grandmother, understood that she wouldn’t be around for long; she forgave Mjongeni because she was older, she had seen life, and she knew she was closer to meeting God. She said nothing when she saw the hired ambulance bring Mjongeni home. She understood what he’d see for himself would be all he needed to realise the consequences of his actions. His condition was now critical.

Siyasanga had no choice but to quit school in 2016 and fill his father’s shoes. They reasoned with Ayanda that it would be just a matter of two years and he’d hopefully be out of school and would take care of everyone. It was supposed to be second nature to him, the life firstborns become accustomed to. Being secondary parents, there is a period where childhood ends without warning. Kites made out of plastic are spontaneously cut off flight in midair. To the floor they crash. Girl children forget their dolls and start to take care of their little siblings.

***

Sometimes rain is kind, and sometimes it is harsh. Harsh rain caught Ayanda with an eagerness. He couldn’t understand how this had become the life he had come to know. Mr Zulu, who, for whatever reason, had become a cog in the wheel of progress. Siyasanga, whose dreams were on halt as a result.

That morning Ayanda had received terrible news, news he hadn’t informed Lungelo about. He’d have to go home the next week soon after his paper on Monday: Andisiwe, now aged 11, had just finished cleaning up after school. As he was off to do his homework, he found his Mama’s motionless, stiff body on the floor. Their 80-year-old grandmother had finally succumbed to the call of death. The call of ash to ash. Relief from a life unfulfilled and anguished. He ran to his father with tears falling down his face, it was a sight he never thought he could possibly ever see. They gave him a phone to call his brothers and deliver the news.

Ayanda saw her face the whole day that Friday, through the beers, and the pool table around him—her hazel eyes and the dying autumn fires in them. Heard her reprimands over the indistinct chatter at the back of the tavern.

“I lost a part of me today, boy,” Ayanda said to Lungelo.

Their chat moved closer to the door of the tavern. The beers seemed to be the only thing that nestled his grief. Lungelo didn’t know how to respond, all he could do was hold his friend’s hand tightly as he talked about the tragedy.

“Worst part of it all is that they sent a child to deliver this news. A child, man!” His eyes were beginning to water so he got up for a cigarette fix.

A fight had ensued inside the tavern unknown to both men. They knew that drunk deeds are seldom processed reasonably. They happen at an instant, almost like instinct and the rest is history. Ayanda quickly moved to break up the fight. He understood that a person led entirely by their emotions was a fool, a fool in danger of jeopardising their own way. When Ayanda got to him, the assailant’s rage was far from soothed. He lunged toward Ayanda who was now in the middle of it all with a knife. He tried to sneak a stab toward his victim, but his metal weapon pierced Ayanda’s guts instead.

Mayhem broke loose, everybody ran away from the scene, no one wanted to be a witness and have to testify. Some ran for fear of the trauma of it all. Lungelo, as the people ran away, looked for his friend and found him lying on the floor.

“HAYI!” he wailed, “not you ntwana yam, no!”

There was nothing he could do. It was too late, even if an ambulance which the tavern owner called arrived on time, little to nothing could be done to save his life.

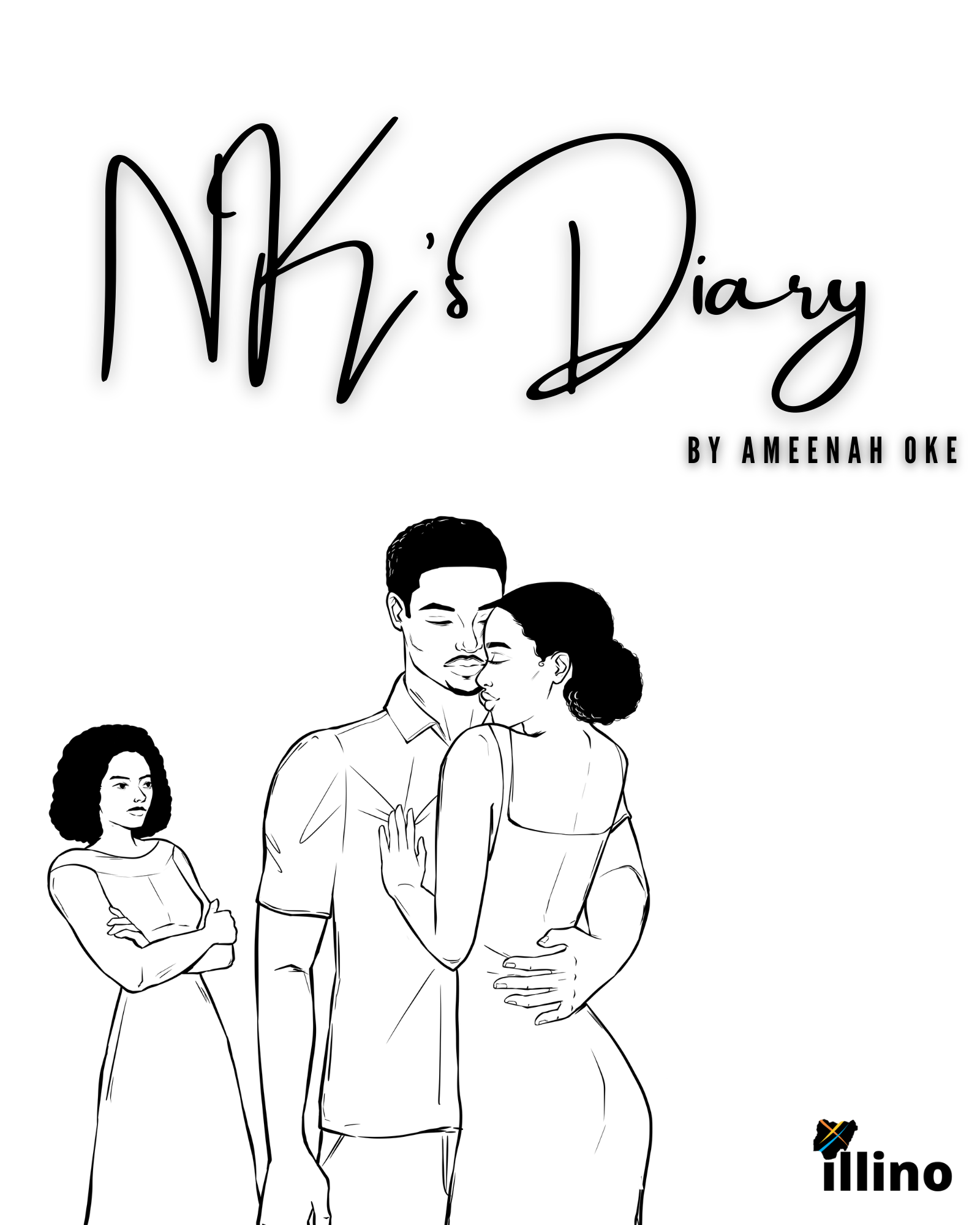

Lindiwe was the last thing Ayanda saw that day. A figment of his imagination, or perhaps the only time we get to see God in the form of the people we care about the most. His sublime perfection, configured and built solely for our hearts. In this moment, he was haunted by the things he didn’t pursue, things that his heart still cried out for. Lindiwe’s curls caressed his face with an intense peace and prepared him for a realm of the next. A comfort that eased his crossing as he took his last breath. The air inside the tavern fought a quiet war, and panic was written on the faces of the few who had the courage to stomach it all. Gasps here and there and hands on top of heads. And all Lungelo could do was cry, helpless.

Though the fire in Ayanda’s life had begun slow, with every passing second it gained momentum and raged with brutality. And today, an injustice was found in the flames.